On the Causes of Persistent Apical Periodontitis. Findings From Endodontic Microsurgery: A Case Report

Published December 06, 2025

J Endod Microsurg. 2025;4: 100019.

Under a Creative Commons license

HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE (AMA Referencing)

Pesántez-Ibarra MJ, Berruecos-Orozco C, Molina-Barrera JK, Ríos-Osorio N, Fernández-Grisales R. On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis. Findings from endodontic microsurgery: A case report. J Endod Microsurg. 2025;4:100019. https://doi.org/10.23999/j.jem.2025.4.1

ABSTRACT

Despite significant advancements in endodontic biomaterials and operative techniques, persistent endodontic infections—frequently attributable to antimicrobial-resistant microorganisms, complex root canal morphology, subobturation of the root canal treatment, or iatrogenic procedural errors—continue to pose a clinical challenge. Orthograde retreatment is generally the preferred intervention; however, when access is precluded by intracanal posts or fixed prosthodontic restorations, endodontic microsurgery (EMS) represents a predictable alternative. This case report details the EMS management of a maxillary central incisor restored with a post and crown, diagnosed as a previously treated tooth with chronic apical abscess. Intraoperative sampling enabled comprehensive histopathological, microbiological, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses. At eight months following EMS procedure, both radiographic and cone beam computed tomographic (CBCT) assessment demonstrated satisfactory periapical healing.

KEYWORDS

Apicectomy, apical deltas, apical periodontitis, endodontic microsurgery, gutta-percha

INTRODUCTION

Intraradicular infection is the main cause of apical periodontitis (AP). Endodontic treatment aims to eradicate infection and prevent recurrence. Successful treatment is shown by bone repair and reduced periapical radiolucency. However, some lesions persist, termed “endodontic failure’’ [1, 2]. Common causes include leakage around obturation (30.4%), missed canals (19.7%), underfilling (14.2%), anatomical complexity (8.7%), and other factors (8.8%) [3, 4]. Occasionally, lesions do not heal despite optimal treatment, often due to true cysts or extraradicular biofilm within inflamed periapical tissue, which may hinder healing [1, 3, 4].

The quality of obturation is crucial for endodontic success. Although gutta-percha and sealer are the standard materials used for root canal filling, overextension beyond the apical foramen can delay periapical healing due to foreign body reactions and inflammation. Untreated canal ramifications, such as apical deltas, lateral canals and isthmuses, serve as bacterial reservoirs and sustain the persistence of AP (PAP) [4]. Kim and Kratchman reported that resection of at least 3 mm of the root apex by endodontic microsurgery (EMS) can eliminate up to 98% of apical ramifications and 93% of lateral canals [5]. In contrast, recurrent apical periodontitis (RAP) refers to the reappearance of the lesion after a period of apparent healing, related to the percolation of tissue fluids or the ingress of bacteria through coronal leakage or root fractures [6, 7].

The present clinical case describes the management of a maxillary incisor using EMS in a patient diagnosed with a previously treated tooth exhibiting a chronic apical abscess. Histopathological, microbiological, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses indicated that the persistence of microorganisms within untreated apical deltas, as well as in transapical gutta-percha, were predisposing factors contributing to the failure of the initial endodontic treatment.

CASE REPORT

This case report has been written according to Preferred Reporting Items for Case reports in Endodontics (PRICE) 2020 guidelines [8].

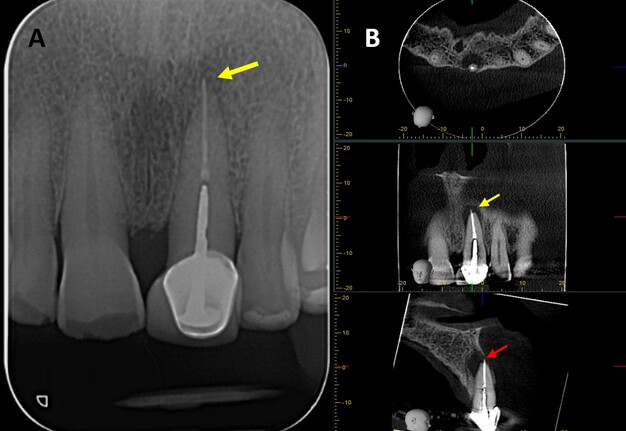

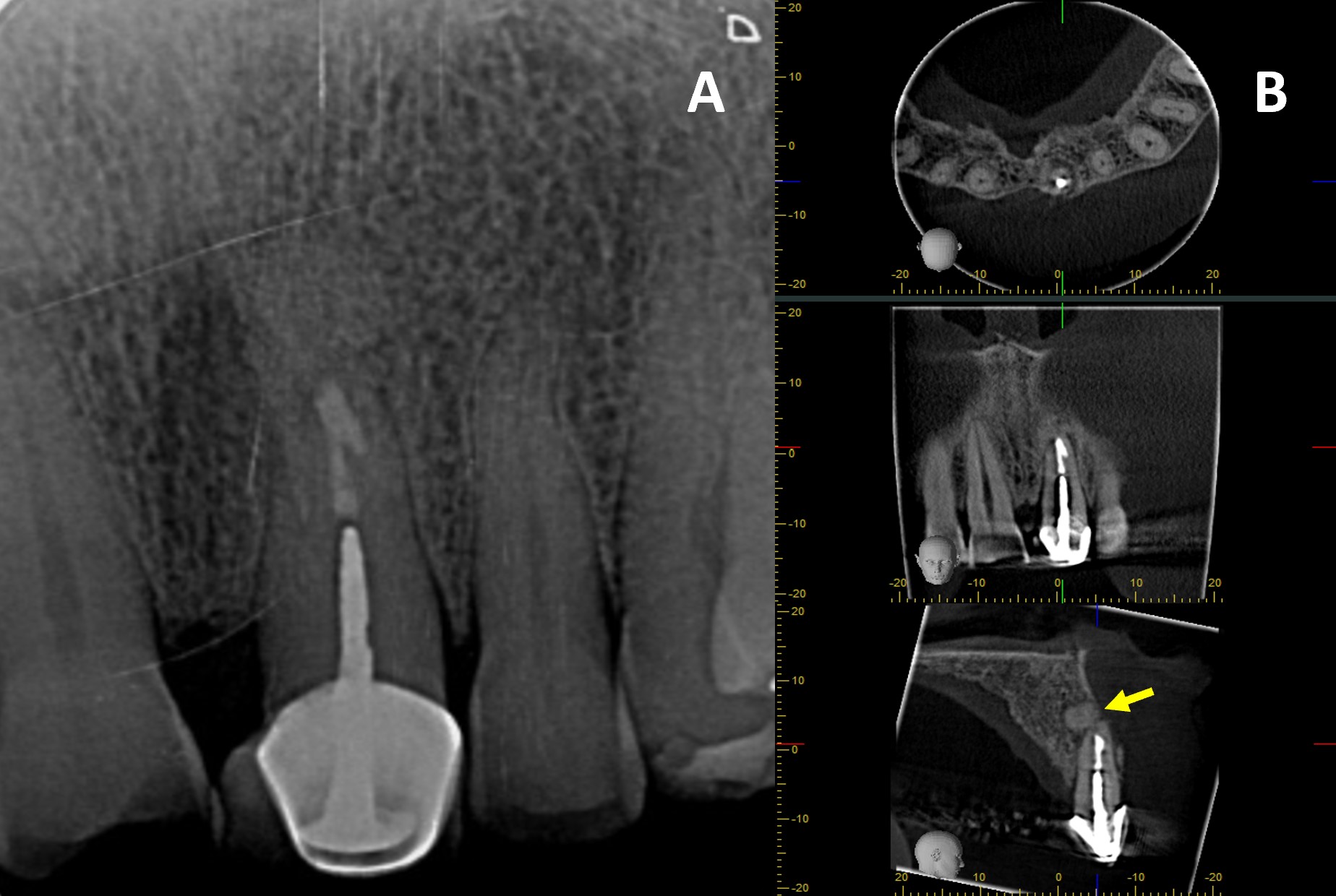

A 76-year-old male with no relevant medical history was referred to the postgraduate endodontics program (CES University Dental Clinic, Sabaneta, Colombia) for evaluation and management of tooth #21. Clinical examination showed a well-fitted metal-ceramic crown, normal probing, grade I mobility, tenderness to palpation and percussion, and fistula on the buccal mucosa. Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) (J. Morita R100, Kyoto, Japan) at 90 mA, 8 kV, FOV 4 cm x 4 cm, and voxel size 0.5 mm showed a single canal with a post in the middle third of the root and extruded obturation material beyond the apex. The periapical lesion was visible on CBCT but not on periapical radiograph (Fig 1 A-B). The established diagnosis was a previously treated tooth with chronic apical abscess affecting tooth #21 (Fig 2-A). The proposed treatment plan was EMS, which was accepted by the patient after obtaining informed consent.

FIGURE 1. (A) Preoperative periapical radiograph of tooth #21, which the presence of a periapical radiolucency is not clearly. (B) Preoperative CBCT of tooth #21, presented in axial, coronal, and sagittal sections, reveals a hypodense area at the apical region consistent with a periapical lesion. The sagittal section demonstrates vestibular bone fenestration, as indicated by the red arrow. The yellow arrow denotes the presence of transapical obturation material in both the periapical radiograph and CBCT, as well as the existence of a post and prosthetic crown.

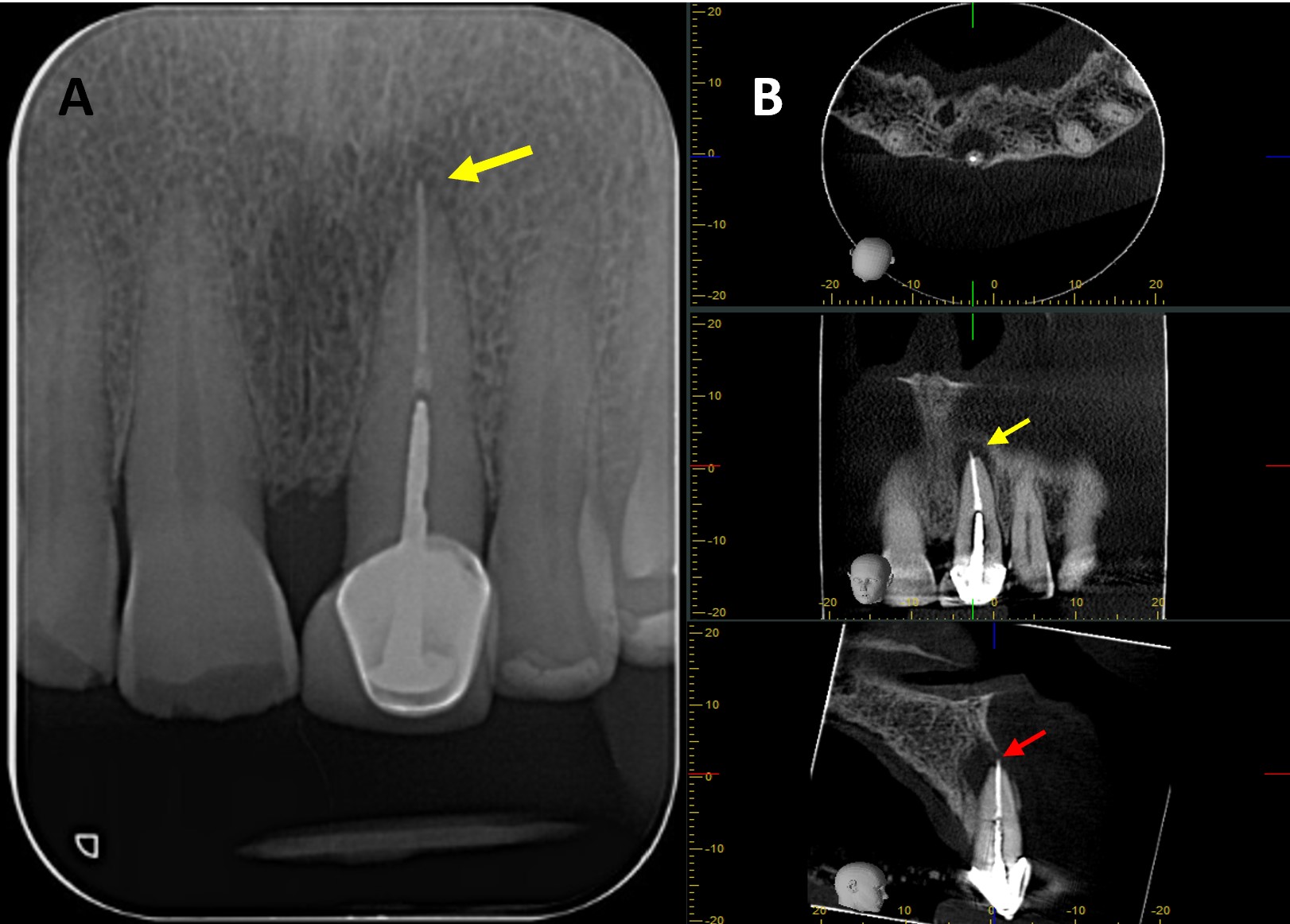

FIGURE 2. (A) Tooth #21 presenting with a sinus tract extending towards the upper labial frenum (indicated by the yellow arrow). (B) Delineation of the flap design on the gingival tissue using a periodontal probe prior to incision. (C) Elevation of a full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap; the periodontal probe is positioned over the apical lesion of tooth #21. (D) Identification of extruded gutta-percha at the apical region (yellow arrow). (E) Placement of the piezoelectric surgical unit with a V-BS5 tip to perform apicectomy. (F) Inspection of the resected root surface, after staining with methylene blue to enhance visualisation. (G) Retrograde cavity preparation using ultrasonic tips. (H) Retrograde cavity Irrigation with 2% chlorhexidine (I) Drying of the retrograde cavity using a capillary tip to ensure optimal conditions for obturation. (J) Evaluation of the retrograde cavity following irrigation and drying procedures. (K) Placement of obturation material (BIO C REPAIR) into the apical cavity using a Mini FP3 instrument. (L) Apical cavity retrofilled. (M) Application of Quirubone bone graft to the surgical site. (N) Adaptation of a Quirumatriz membrane over the grafted area to facilitate guided tissue regeneration. (O) Repositioning of the flap and closure with simple interrupted sutures.

Under local anesthesia, three cartridges of 4% articaine with 1:100.000 epinephrine (Septodont, Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, France) were infiltrated for nerves block (anterior superior alveolar and nasopalatine) at tooth #21. Incisions were marked with a periodontal probe (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, USA) (Fig 2-B), and using an operating microscope (ZUMAX OMS 2350, Zumax Medical, Suzhou New District, China) at 8x magnification, a full-thickness submarginal triangular flap was raised between teeth #21 and #22 with a #15C scalpel blade (Zhejiang Mediunión Healthcare Group Co., Ltd, Zhejiang, China) (Fig 2-C). Once the flap was elevated with a mini-busser (Marthe®, Bucaramanga, Colombia), transapical gutta-percha (Fig 2-D) and periapical inflammatory tissue were identified and removed with Lucas and Gracey curettes (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, USA) for histopathological analysis.

The root surface was stained with methylene blue (ADS Pharma, Bogotá, Colombia), and at 16x magnification, the absence of fracture was confirmed. Subsequently, a 3 mm apicectomy was performed (Fig 2-E) with a piezoelectric device (Acteon, Satelec, France) at medium power and copious irrigation using distilled water. The apical fragment was immediately immersed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution in a sterile container and stored under aseptic conditions until processing for SEM analysis. Local haemostasis was achieved with epinephrine pellets [0.55 mg] (Racellet #3 Pascal, Washington, USA), and after staining the resected root surface with methylene blue, the previously treated root canal was located (Fig 2-F) and retro-prepared to a depth of 3 mm using an E32D ultrasonic tip (NSK, Tokyo, Japan) operated with the Acteon P5 Newtron ultrasonic unit (Satelec, France) (Fig 2-G) at power setting 10 with copious irrigation.

After confirming retro-preparation with a round micro-mirror MM4 (Hu-Friedy, Chicago, USA) at 16x magnification, the cavity was disinfected with 2% chlorhexidine (Wescohex, La Estrella, Colombia) for 15 seconds using a 5 ml syringe and 30 G monojet needle (Ultradent, South Jordan, USA) (Fig 2-H), then dried with a capillary tip (Azdent, Zhengzhou, China) (Fig 2-I) and inspected prior to retro-obturation (Fig 2-J). For this purpose, Bio-C Repair bioceramic cement (Angelus, Londrina, Brazil) was placed using a mini FP3 (Marthe, Bucaramanga, Colombia) (Fig 2-K) and compacted to achieve complete obturation (Fig 2-L).

Finally, guided tissue regeneration was carried out using [1g] Quirubone bone graft with particle size [0.25-0.5 mm] (Cellstech, Itagüí, Colombia) and Quirumatriz membrane [15 x 20 mm] (Cellstech, Itagüí, Colombia) (Fig 2-M and 2-N). The flap was repositioned and sutured with resorbable Vicryl 5/0 (Vicryl Plus, Ethicon, India) (Fig 2-O). Postoperative care included amoxicillin [875mg/12h/5days], meloxicam [7.5mg/12h/3days], and mouth rinses with chlorhexidine [0.2%] (Clorhexol, Farpaq, Cali, Colombia) 10 ml-rinse for 60 s twice-a-day (every 12 h) for 7 days. Radiographic and tomographic assessment at eight months demonstrated ongoing healing of the affected periapical tissues. Furthermore, it was observed that the ultrasonic retropreparation did not follow the original trajectory of the root canal, as a slight deviation towards the distal wall was noted. In addition, the retrograde obturation material remained well positioned throughout the follow-up period, thereby supporting the favourable progression of periapical tissue repair (Fig 3 A-B).

PROTOCOL FOR HISTOPATHOLOGICAL EVALUATION OF PERIAPICAL TISSUE

Excised periapical tissue was immediately fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin to preserve cellular and tissue architecture; subsequently, following fixation, the specimens were dehydrated through graded alcohols, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax. Thereafter, paraffin blocks were sectioned at a thickness of 3-5 μm using a microtome, and the resulting sections were routinely stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to facilitate the assessment of general morphology, the identification of inflammatory cell infiltrates and granulomatous tissue, as well as the determination of the presence or absence of an epithelial lining.

PROTOCOL FOR SCANNING ELECTRON MICROSCOPY (SEM)

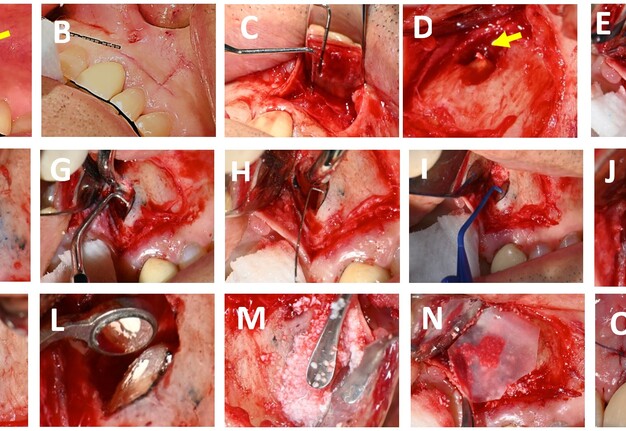

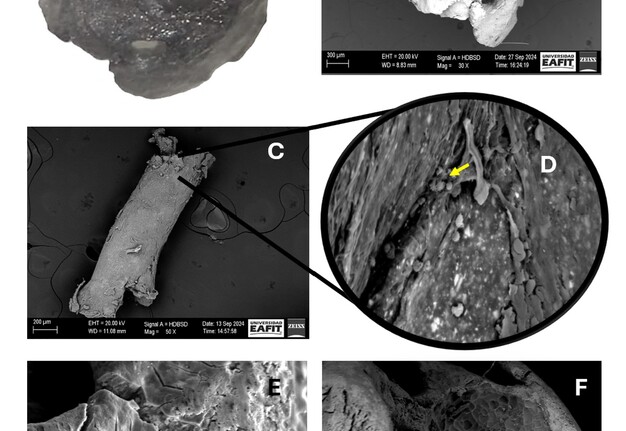

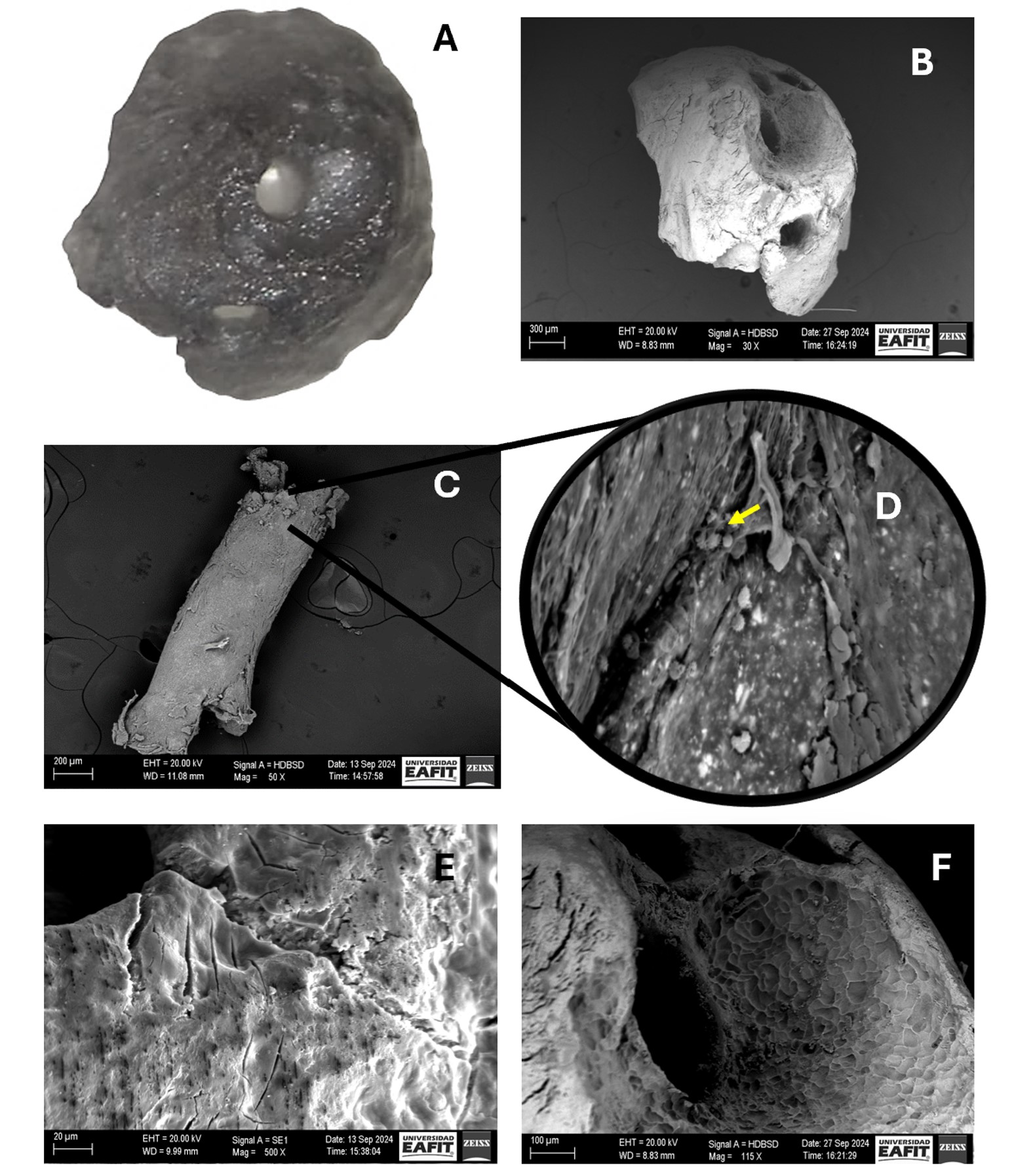

The resected apex and the extruded gutta-percha were dehydrated in increasing ethanol concentrations (10-99.6%) (Freire Mejía, Cuenca, Ecuador). Subsequently, samples were coated with gold-palladium using a Sputter Coater model SC7620 (Quorum Tech, UK) for 180 seconds to achieve a 5-10nm layer, and examined with an EVO 10 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Weimar, Germany) under the following operating conditions: acceleration voltage 20,000 KV, temperature 20°C, and humidity 65% (Fig 4 A-F).

FIGURE 4. Apical fragment visualised by (A) surgical microscope at 30x magnification and by (B) scanning electron microscopy (SEM) at 30x magnification. (C) Transapical gutta-percha visualised at 50x magnification. (D) Overview of image C at 1000x magnification (yellow arrow indicates the presence of coccoid-shaped bacteria). (E and F) indicate the presence of microfissures and external root resorption in the apical portion, respectively.

PROTOCOL FOR MICROBIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS

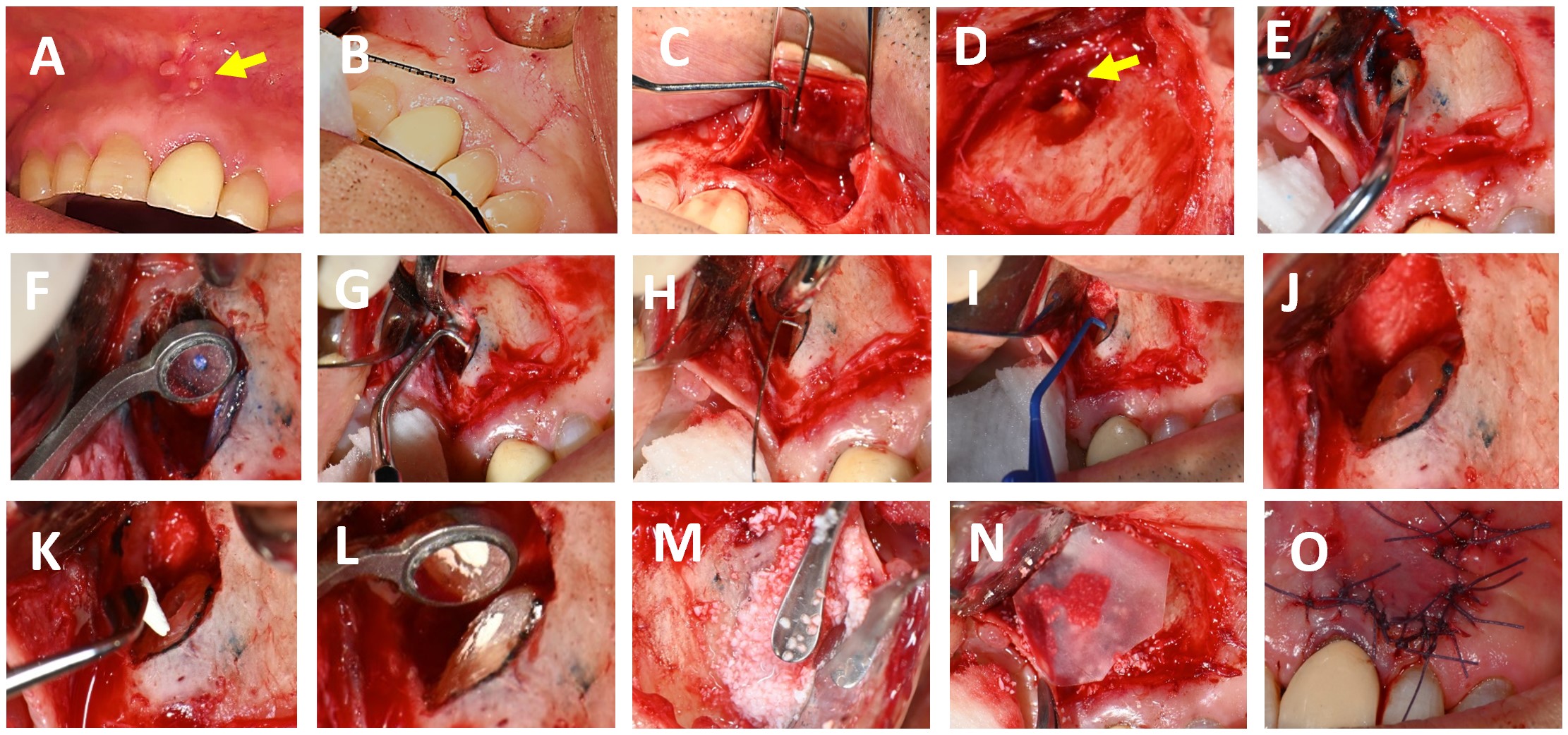

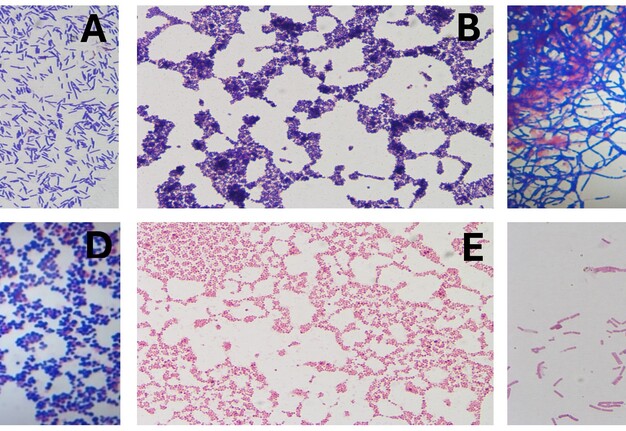

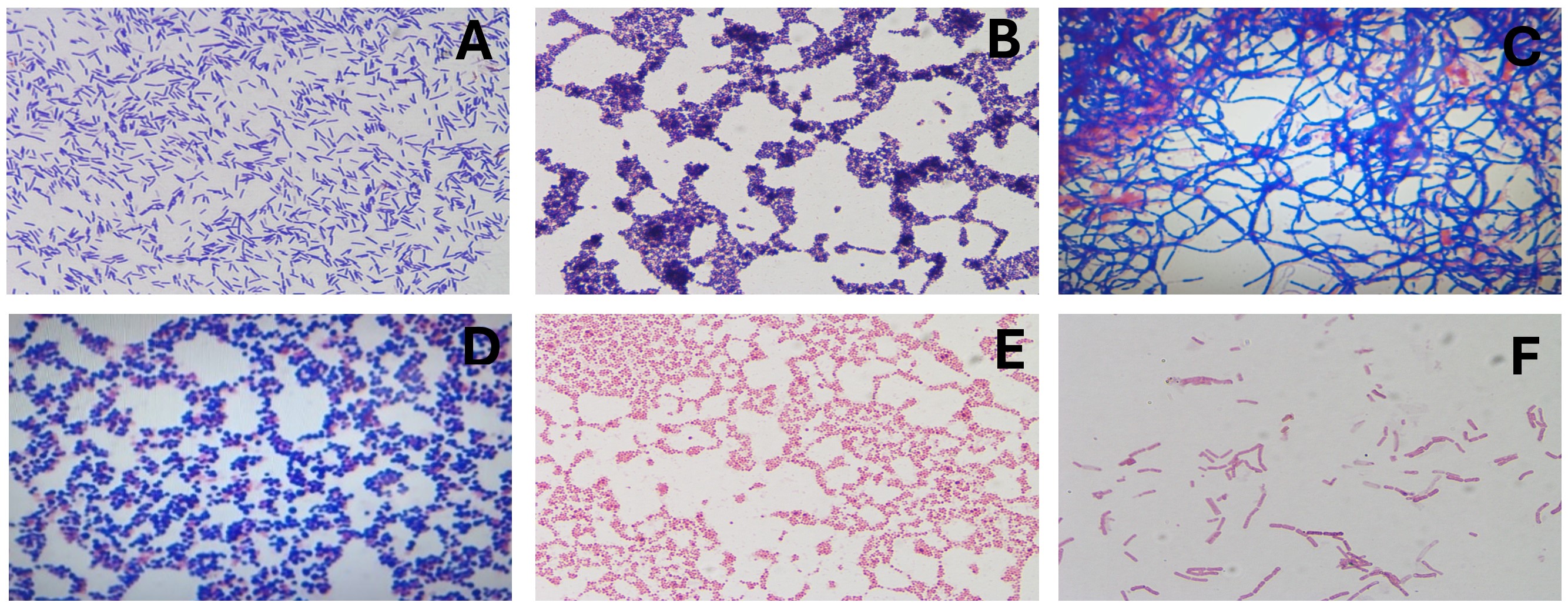

Five samples—root apex, gutta-percha, and three from the lesion were stored in BHI broth and Stuart medium for multi-species microbiological analysis. Cultures were grown on McConkey, blood, and soy agar under aerobic and anaerobic conditions at 37°C in an incubator for 24 hours. Colonies were identified, heat-fixed, and Gram stained for microscopic examination (Fig 5 A-F).

FIGURE 5. Microbiological findings. (A) Gram-positive bacilli; (B) Gram-positive staphylococci; (C) At the root apex, Gram-positive microbiota, streptobacilli, and streptococci were identified; (D) In the sample obtained by aspiration of periapical exudate under aerobic conditions, (E) Gram-negative staphylococci and (F) Gram-negative streptobacilli.

RESULTS FROM HISTOPATHOLOGICAL, MICROBIOLOGICAL, AND SEM ANALYSES

Histopathological Findings

Microscopic examination of the periapical tissue revealed granulomatous inflammation, predominantly composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages, without evidence of epithelial lining.

SEM Findings

SEM analysis identified multiple apical foramina harbouring bacterial colonies, as well as microcracks and areas of external root resorption on the resected apex and extruded gutta-percha.

Microbiological Findings

Cultures from the root apex, extruded gutta-percha, and periapical lesion yielded mixed populations of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including streptococci and staphylococci, under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions.

DISCUSSION

EMS is a recognised treatment option for teeth with PAP when conventional endodontic treatment or retreatment is not possible [5]. In the present case, EMS was selected over orthograde retreatment due to the presence of a well-adapted prosthetic crown and a long intraradicular post, which would have made post removal technically demanding, time-consuming, and increased the risk of root fracture. By contrast, EMS provided direct access to the apical region, enabling effective debridement while preserving the existing restoration. This decision is supported by evidence reporting success rates for EMS ranging from 85% to 97.6% over follow-up periods of 1.5 to 5 years [9], particularly in cases where orthograde retreatment is impractical. Although the follow-up period in this case was shorter, the absence of clinical symptoms and radiographic findings indicated periapical healing in process, as confirmed by periapical radiographs and CBCT.

CBCT has been recommended for the diagnosis, planning and follow-up in endodontics, due to its three-dimensional imaging, which overcomes the limitations of traditional periapical radiograph (PR) [10, 11]. In this case, CBCT identified a periapical lesion that was not visible on PR and enabled more precise surgical planning. Furthermore, the tomographic follow-up findings suggested ongoing periapical healing. Compared to PR, it may have been mistakenly considered a complete healing, which supports the use of CBCT for longer-term follow-up of this case.

In addition to its superior spatial resolution, CBCT provides volumetric data that allow clinicians to assess the extent and morphology of periapical lesions with greater accuracy. This is particularly valuable in cases where conventional radiographs fail to reveal subtle changes in bone density or lesion progression. The ability to visualise anatomical structures in multiple planes enhances diagnostic confidence and facilitates the identification of complex root canal systems, accessory canals, and bone fenestrations. Moreover, CBCT is instrumental in monitoring the healing process post-operatively, as it can detect early signs of bone regeneration and residual pathology that may not be apparent on two-dimensional images. The literature consistently supports the integration of CBCT into routine endodontic practice, especially for cases requiring detailed assessment and long-term follow-up, thereby improving clinical outcomes and reducing the risk of misdiagnosis [11].

Natural ramifications of the main root canal, including lateral, accessory, and secondary canals, as well as apical deltas, are recognised as significant contributors to PAP. These anatomical complexities are especially prevalent in maxillary central incisors, with reported frequencies ranging from 46% to 62%, predominantly located within the final millimetres of the apical canal [1, 14]. The presence of such intricate canal networks poses a considerable challenge to conventional endodontic therapy, as these regions often harbour microbial communities that are inaccessible to standard instrumentation and irrigation techniques [4, 12, 13]. Consequently, bacteria may persist within these untreated ramifications, leading to ongoing periapical inflammation and failure of root canal treatment.

To address this anatomical challenge, a 3 mm apical resection during EMS is advocated, as it has been demonstrated to effectively remove most apical ramifications and thereby reduce the risk of persistent infection [5]. In the present case, SEM findings confirmed the existence of four apical foramina containing microorganisms that had not been eliminated by the initial endodontic procedure. This observation underscores the importance of recognising and surgically managing complex apical anatomy to achieve successful treatment outcomes. Failure to adequately address these anatomical features may result in continued periapical disease, even when other aspects of the treatment are performed to a high standard.

Preoperative PR and CBCT showed extruded endodontic obturation material. Subsequent SEM analysis identified bacterial colonisation on the gutta-percha. Although gutta-percha is widely regarded as a biocompatible material, insufficient disinfection prior to obturation has been recognised as a prognostic factor that may negatively influence treatment outcomes—a circumstance that appears relevant in this case [4, 11]. Furthermore, Ørstavik’s findings demonstrated that the success rate of endodontic treatment is significantly affected by the position of the root canal filling: when obturation ended within 2 mm of the radiographic apex, the success rate reaches 94%, whereas overextension of the filling material beyond the apex reduces the success rate to 76% [15]. These observations underscore the importance of precise obturation and stringent infection control protocols in achieving optimal periapical healing.

Follow-up PR and CBCT confirmed the presence of retrofilling material. Bio-C Repair, a bioceramic cement containing tricalcium silicate, dicalcium silicate, tricalcium aluminate, calcium oxide, silicon oxide, zirconium oxide, polyethylene glycol, and iron oxide, was used. Its bioactivity encourages reparative cell growth and supports periapical healing [16]. Bio-C Repair is highly biocompatible and forms hydroxyapatite when in contact with tissue fluids, promoting osteoinduction and osteoconduction, and facilitating bone regeneration and repair of periapical tissues after endodontic microsurgery. Its ready-to-use presentation and expansion on setting improve adaptation and chemical sealing to dentine, reducing leakage and reinfection risk [16, 17]. Although a slight deviation of retropreparation was observed, this variation is not considered clinically significant as it did not compromise the adaptation or sealing ability of the retrofilling material, nor the biological processes essential for periapical healing [5].

In this case, AP was diagnosed as a periapical granuloma, a common lesion linked to pulpal necrosis and chronic periapical inflammation [4]. Histologically, it consists of granulomatous tissue with fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and mainly inflammatory cells like lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and sometimes multinucleated giant cells. The absence of epithelial lining allows differentiation from periapical cysts, which is important for therapeutic management [18]. Clinically, periapical granulomas are usually asymptomatic early on, but may cause mild pain, percussion tenderness, or a sinus tract if inflammation is exacerbated. Radiographically, they appear as poorly defined radiolucent lesions at the tooth apex and may show bone resorption [5]. The reported prevalence of periapical granuloma varies greatly, from 9.3% to 87.1% of periapical lesions, depending on the population and diagnostic criteria. Multicenter studies confirm that most chronic periapical lesions are granulomas, followed by cysts and abscesses [4, 18]. Treatment involves removing the infection through conventional endodontics or EMS, allowing periapical tissue repair. Success relies on thorough canal disinfection and filling with biocompatible materials. Ongoing clinical and radiographic reviews are essential to confirm healing and detect recurrence [5, 18].

SEM images showed microcracks within the apical region, most plausibly attributable to mechanical stresses induced during canal instrumentation or to artefacts arising from sample dehydration during specimen processing [19, 20]. The identification of these microstructural defects, together with evidence of external root resorption, is of considerable clinical significance. Such alterations in the root surface architecture may facilitate the ingress of pathogenic microorganisms into the periapical tissues, thereby compromising the healing process, prolonging inflammation, and substantially increasing the likelihood of endodontic treatment failure. Accordingly, the meticulous execution of operative procedures, combined with a rigorous correlation of SEM findings with clinical and radiographic assessments, is imperative to ensure precise diagnosis and optimal management of PAP [21, 22].

Microbiological analysis of persistent apical periodontitis showed a range of bacteria, mainly Gram-positive and Gram-negative types, especially streptococci and facultative anaerobes. Enterococcus faecalis has been identified as one of the principal agents in persistent cases, owing to its ability to survive in nutritionally adverse environments and to form resistant biofilms. The formation of bacterial biofilms, both intra- and extraradicular, complicates the complete elimination of microorganisms by conventional treatments and significantly contributes to endodontic failure and lesion recurrence [4, 23, 24]. Although only bacterial genera were identified in this case, the findings match existing literature, highlighting the need for advanced therapies and proper microbiological monitoring to improve outcomes.

CONCLUSION

The identification of bacterial colonization within uninstrumented apical canal ramifications, as well as the presence of adherent extruded gutta-percha, clarifies the pathogenesis underlying the initial endodontic failure. These observations underscore the clinical significance of recognising apical ramifications as potential reservoirs for persistent infection, highlight the importance of meticulous control over material extrusion during treatment, and emphasise the value of multimodal analysis in complex diagnostic scenarios. Collectively, these findings reinforce the relevance of EMS in managing anatomically challenging or refractory cases of apical periodontitis, particularly when conventional orthograde retreatment is contraindicated or impracticable due to intracanal posts or fixed prosthodontic restorations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the endodontic residents who meticulously documented the case and made this case report possible.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors deny any conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

REFERENCES (24)

-

Jang JH, Lee JM, Yi JK, et al. Surgical endodontic management of infected lateral canals of maxillary incisors. Restor Dent Endod. 2015;40(1):79. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2015.40.1.79

-

Babeer A, Bukhari S, Alrehaili R, et al. Microrobotics in endodontics: A perspective. Int Endod J. 2024;57(7):861-871. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.14082

-

Bucchi C, Rosen E, Taschieri S. Non‐surgical root canal treatment and retreatment versus apical surgery in treating apical periodontitis: A systematic review. Int Endod J. 2023;56(S3):475-486. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13793

-

Nair PNR. On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis: a review. Int Endod J. 2006;39(4):249-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2591.2006.01099.x

-

Kim S, Kratchman S. Modern endodontic surgery concepts and practice: A review. J Endod. 2006;32(7):601-623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2005.12.010

-

Buonavoglia A, Zamparini F, Lanave G, et al. Endodontic microbial communities in apical periodontitis. J Endod. 2023;49(2):178-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2022.11.015

-

Ricucci D, Siqueira JF. Recurrent apical periodontitis and late endodontic treatment failure related to coronal leakage: A case report. J Endod. 2011;37(8):1171-1175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2011.05.025

-

Nagendrababu V, Chong BS, McCabe P, et al. PRICE 2020 guidelines for reporting case reports in Endodontics: A consensus-based development. Int Endod J. 2020;53(5):619-626. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13285

-

Truschnegg A, Rugani P, Kirnbauer B, et al. Long-term follow-up for apical microsurgery of teeth with core and post restorations. J Endod. 2020;46(2):178-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2019.11.002

-

Ríos-Osorio N, Quijano-Guauque S, Briñez-Rodríguez S, et al. Cone-beam computed tomography in endodontics: from the specific technical considerations of acquisition parameters and interpretation to advanced clinical applications. Restor Dent Endod. 2023 11;49(1):e1. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2024.49.e1

-

Fernández R, Cadavid D, Zapata SM, et al. Impact of three radiographic methods in the outcome of nonsurgical endodontic treatment: A five-year follow-up. J Endod. 2013;39(9):1097-1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2013.04.002

-

Wada M, Takase T, Nakanuma K, et al. Clinical study of refractory apical periodontitis treated by apicectomy. Part 1. Root canal morphology of resected apex. Int Endod J. 1998;31(1):53-56.

-

Arnold M, Ricucci D, Siqueira JF. Infection in a complex network of apical ramifications as the cause of persistent apical periodontitis: A case report. J Endod. 2013;39(9):1179-1184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joen.2013.04.036

-

Adorno CG, Yoshioka T, Suda H. Incidence of accessory canals in Japanese anterior maxillary teeth following root canal filling ex vivo. Int Endod J. 2010;43(5):370-176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2591.2010.01688.x

-

Ørstavik D. Endodontic treatment of apical periodontitis. In: Ørstavik D, editor. Essential endodontology: Prevention and treatment of apical periodontitis. 3rd ed. Wiley; 2019. p. 313-344.

-

Queiroz MB, Inada RNH, Jampani JLDA, et al. Biocompatibility and bioactive potential of an experimental tricalcium silicate‐based cement in comparison with Bio‐C repair and MTA Repair HP materials. Int Endod J. 2023;56(2):259-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13863

-

Benetti F, Queiroz ÍOA, Cosme-Silva L, et al. Cytotoxicity, biocompatibility and biomineralization of a new ready-for-use bioceramic repair material. Braz Dent J. 2019;30(4):325-332. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6440201902457

-

Banomyong D, Arayasantiparb R, Sirakulwat K, et al. Association between clinical/radiographic characteristics and histopathological diagnoses of periapical granuloma and cyst. Eur J Dent. 2023;17(4):1241-1247. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-1759489

-

Jamleh A, Komabayashi T, Ebihara A, et al. Root surface strain during canal shaping and its influence on apical microcrack development: a preliminary investigation. Int Endod J. 2015;48(12):1103-1111. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12406

-

Versiani MA, Cavalcante DM, Belladonna FG, et al. A critical analysis of research methods and experimental models to study dentinal microcracks. Int Endod J. 2022;55(S1):178-226. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.13660

-

Felippe WT, Ruschel MF, Felippe GS, et al. SEM evaluation of the apical external root surface of teeth with chronic periapical lesion. Aust Endod J. 2009;35(3):153-157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4477.2009.00165.x

-

Chieruzzi M, Pagano S, De Carolis C, et al. Scanning electron microscopy evaluation of dental root resorption associated with granuloma. Microsc Microanal. 2015;21(5):1264-1270. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1431927615014713

-

Sun X, Yang Z, Nie Y, Hou B. Microbial communities in the extraradicular and intraradicular infections associated with persistent apical periodontitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;11:798367. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2021.798367

-

Takahama A Jr, Rôças IN, Faustino ISP, et al. Association between bacteria occurring in the apical canal system and expression of bone-resorbing mediators and matrix metalloproteinases in apical periodontitis. Int Endod J. 2018;51(7):738-746. https://doi.org/10.1111/iej.12895